A DIVERSIFIED PORTFOLIO

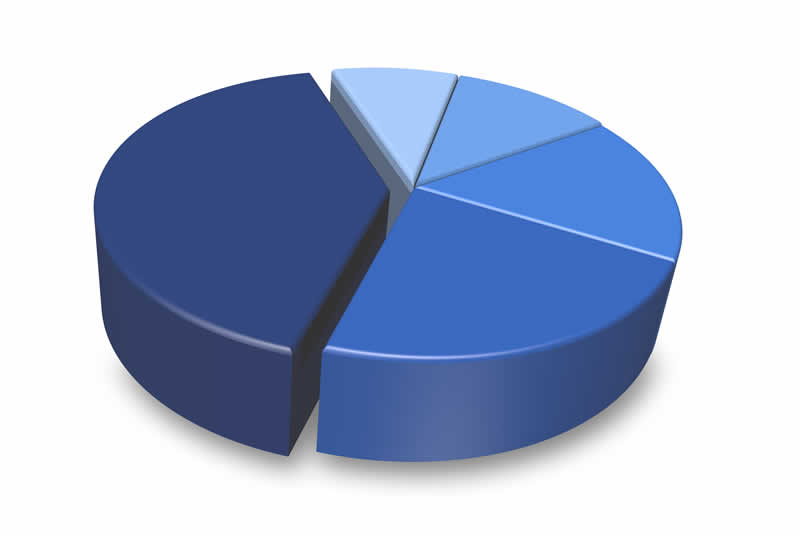

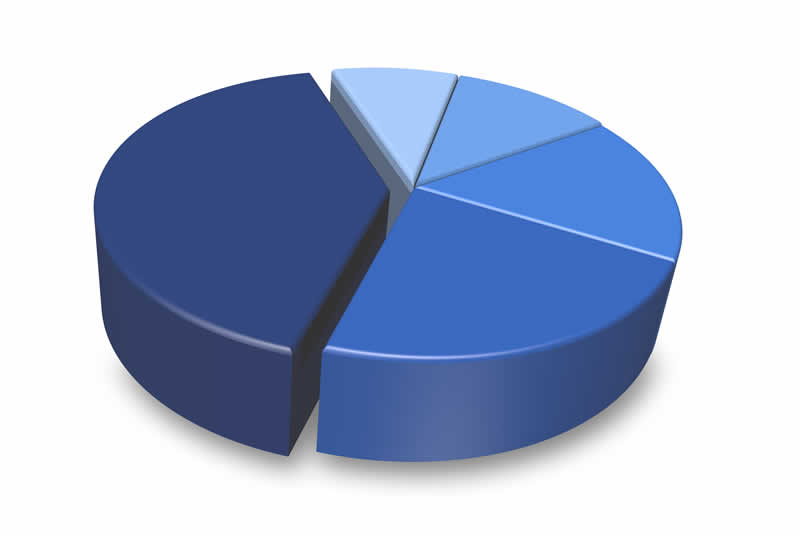

Similar to financial assets, we protect against impacts to our water-supply resources by diversifying our supply portfolio. In the context of southeastern Ventura County, supplies are generally divided into two main buckets: imported water and local water. While imported water from Northern California is an important part of our portfolio (about half our drinking water supply and a third overall), it is outside our sphere of influence; we’ll always be at the mercy of factors over which we have no control, such as weather, rate-setting by other agencies, and infrastructure demands. To offset this, Camrosa has invested more than $30 million in ratepayer and grant funds over the last 20 years to develop local projects and infrastructure that transfer demand from imported water to water we produce right here, in our own backyard.

Similar to financial assets, we protect against impacts to our water-supply resources by diversifying our supply portfolio. In the context of southeastern Ventura County, supplies are generally divided into two main buckets: imported water and local water. While imported water from Northern California is an important part of our portfolio (about half our drinking water supply and a third overall), it is outside our sphere of influence; we’ll always be at the mercy of factors over which we have no control, such as weather, rate-setting by other agencies, and infrastructure demands. To offset this, Camrosa has invested more than $30 million in ratepayer and grant funds over the last 20 years to develop local projects and infrastructure that transfer demand from imported water to water we produce right here, in our own backyard.

Over the past 20 years, we’ve reduced our reliance on imported water from being 85 percent of our water portfolio to just about one-third of our total supply (potable and non-potable). But despite its vulnerabilities, the State Water Project is a massive system upon which two thirds of the state relies for drinking water, so there is significant incentive to keep it operable and secure. Local resources are cheaper and within our sphere of control, but they too are ultimately subject to the whims of nature, and to disconnect from the State Water Project altogether would risk being entirely dependent on local resources—that old eggs-in-a-single-basket thing.

And although it’s the most expensive source of drinking water, imported water is also, aside from the RMWTP, the highest-quality water we produce. The technology exists to treat local water to match the quality of imported water, but it would make the two waters similar in cost. In fact, Camrosa could, in theory, turn every drop of water we produce into perfectly pure, deionized H20, but those drops would be prohibitively expensive. It is the philosophy of our Board and district to balance quality and cost, and it is our ability to blend imported water with local groundwater that allows us to do just that.

Similar to financial assets, we protect against impacts to our water-supply resources by diversifying our supply portfolio. In the context of southeastern Ventura County, supplies are generally divided into two main buckets: imported water and local water. While imported water from Northern California is an important part of our portfolio (about half our drinking water supply and a third overall), it is outside our sphere of influence; we’ll always be at the mercy of factors over which we have no control, such as weather, rate-setting by other agencies, and infrastructure demands. To offset this, Camrosa has invested more than $30 million in ratepayer and grant funds over the last 20 years to develop

Similar to financial assets, we protect against impacts to our water-supply resources by diversifying our supply portfolio. In the context of southeastern Ventura County, supplies are generally divided into two main buckets: imported water and local water. While imported water from Northern California is an important part of our portfolio (about half our drinking water supply and a third overall), it is outside our sphere of influence; we’ll always be at the mercy of factors over which we have no control, such as weather, rate-setting by other agencies, and infrastructure demands. To offset this, Camrosa has invested more than $30 million in ratepayer and grant funds over the last 20 years to develop  The District’s largest operating expense is the cost of imported water via the State Water Project (SWP). Between the unpredictability of supply and the unreliability of the conveyance system, it is also the District’s biggest vulnerability.

The District’s largest operating expense is the cost of imported water via the State Water Project (SWP). Between the unpredictability of supply and the unreliability of the conveyance system, it is also the District’s biggest vulnerability. Camrosa operates thirteen wells in four aquifers that produce fully half the drinking water we deliver. We have, for more than fifty years, operated those wells in response to basin conditions—when groundwater levels are high, we pump freely. When they fall, we’re more conservative. As levels of various water constituents fluctuate, we blend with more imported water to balance them out. This adaptive management has allowed Camrosa to steadily increase the proportion of the water supplies we develop in this area while remaining good stewards of our local resources.

Camrosa operates thirteen wells in four aquifers that produce fully half the drinking water we deliver. We have, for more than fifty years, operated those wells in response to basin conditions—when groundwater levels are high, we pump freely. When they fall, we’re more conservative. As levels of various water constituents fluctuate, we blend with more imported water to balance them out. This adaptive management has allowed Camrosa to steadily increase the proportion of the water supplies we develop in this area while remaining good stewards of our local resources.